Problématiser, et non résoudre, ne pas s’arrêter à des contradictions construites. Ce sont des paresses de la pensée qui permettent de simplifier et démembrer la situation. (Cache les autres possibilités, arrive à un mur) Poser le problème autrement. Comment la neutralité est construite: et même existe-elle? Interroger le dispositif de rencontre: Travailler des intérets. Contre-proposition: disposition génératif, inflexions sur les intérets de chacun. Donner du concret à la situation.

Isabelle Stengers

Entretien avec la philosophe Isabelle Stengers autour de son livre "Réactiver le sens commun”, Mediapart, 15.03.2020

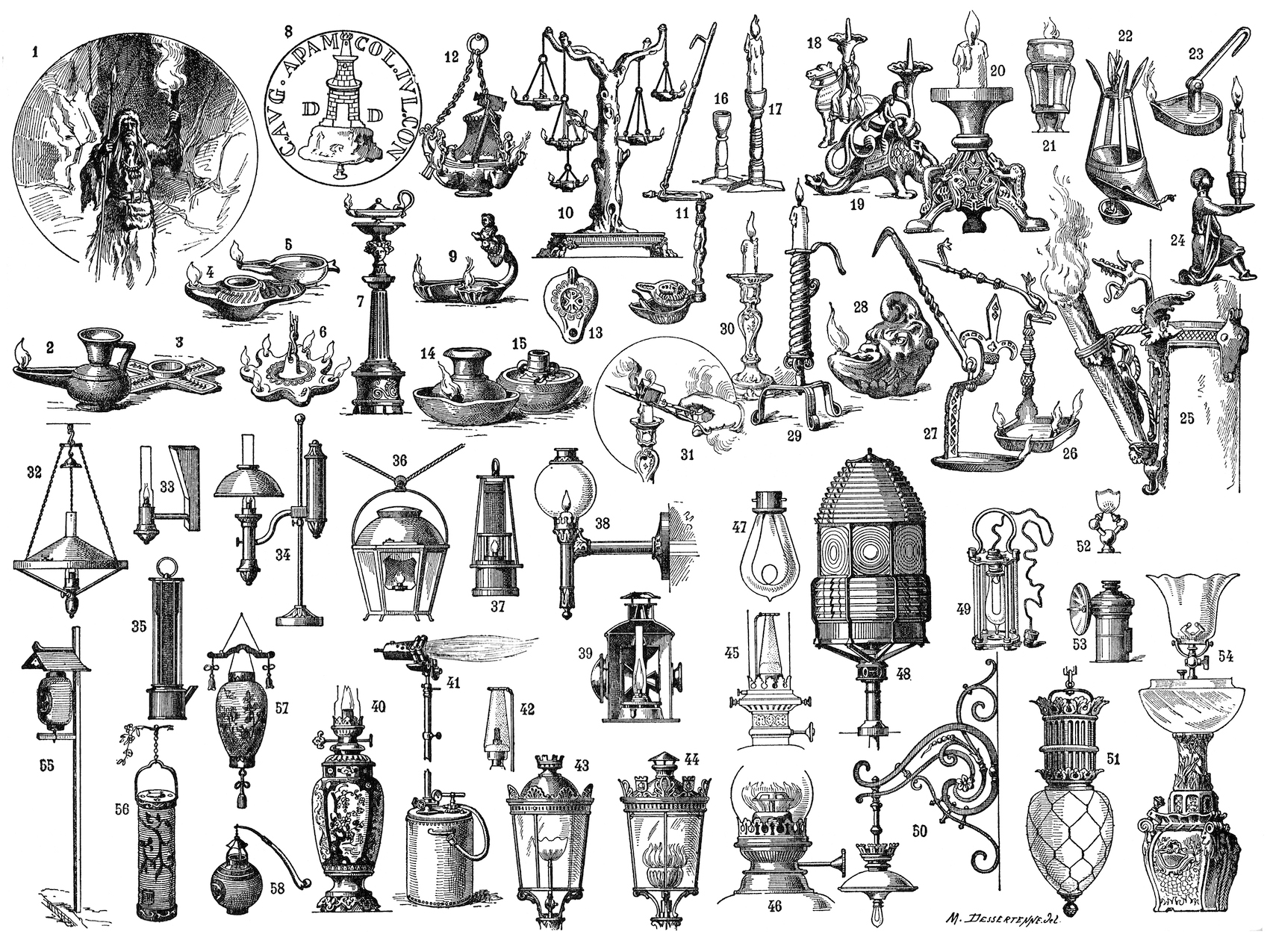

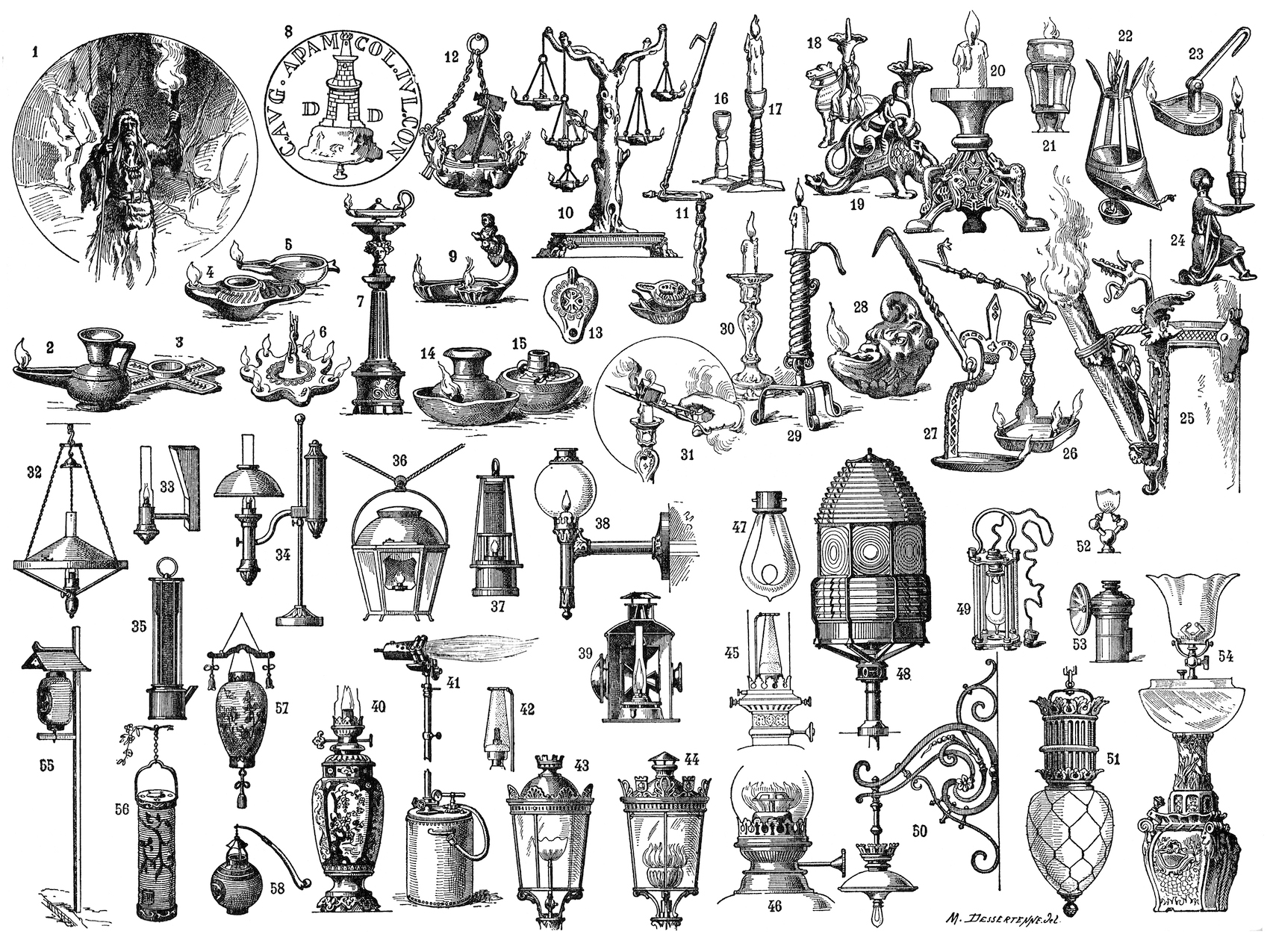

Parabole du réverbère: Un homme tourne autour d’un réverbère pendant la nuit un autre passe et lui demande ce qu’il cherche. L’autre lui répond ses clefs. L’homme se mets alors à chercher avec lui ne trouve pas les clefs. Il lui demande alors: Est-ce que vous êtes sur de les avoir perdu ici? L’autre lui répond: Non pas du tout mais c’est seul endroit qui est éclairé.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

‘Balloonomania’ swept Britain in the last quarter of the 18th century, thanks largely to the exploits of the early aeronaut Vincenzo Lunardi. Following in the footsteps of the Montgolfier brothers in France, Lunardi arrived in London from Italy in the early 1780s determined to demonstrate the wonders of balloon-powered flight to the public. On the morning of 15 September 1784 nearly 200,000 people watched as Lunardi launched into the air in a hydrogen balloon, accompanied by his companions a dog, a cat and a pigeon, and drifted northwards for 24 miles before landing safely in Hertfordshire. For the next 50 years or so balloon flights across Britain became all the rage, drawing huge and expectant crowds whenever news of a launch was published, influencing science, literature and even fashions in the process. Pictured here is a public display of Lunardi’s balloon at the Pantheon in London, shortly after his maiden flight.

‘Balloonomania’ swept Britain in the last quarter of the 18th century, thanks largely to the exploits of the early aeronaut Vincenzo Lunardi. Following in the footsteps of the Montgolfier brothers in France, Lunardi arrived in London from Italy in the early 1780s determined to demonstrate the wonders of balloon-powered flight to the public. On the morning of 15 September 1784 nearly 200,000 people watched as Lunardi launched into the air in a hydrogen balloon, accompanied by his companions a dog, a cat and a pigeon, and drifted northwards for 24 miles before landing safely in Hertfordshire. For the next 50 years or so balloon flights across Britain became all the rage, drawing huge and expectant crowds whenever news of a launch was published, influencing science, literature and even fashions in the process. Pictured here is a public display of Lunardi’s balloon at the Pantheon in London, shortly after his maiden flight.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

UN AUTRE MONDE

Bientôt l’exposition

L’Atomium, que l’on aurait pu appeler Moléculium, représente, agrandie monstrueusement, l’image que l’on se fait d’une structure moléculaire. Cette image sert de base en Science à des spéculations, des raisonnements.

L’expression «tout se passe comme si» revient souvent dans les ouvrages de physique. Ce qui signifie que nous aurions tort de croire qu’une structure moléculaire (un ensemble d’atomes régi par des interactions) est telle dans la réalité. En l’état actuel des ressources scientifiques, cette réalité n’est pas susceptible d’être photographiée. Il est beaucoup plus difficile de trouver une molécule qu’une aiguille dans une botte de foin. Le plus petit morceau de matière, avant de cesser d’être une matière, défie les microscopes.

Je pense d’ailleurs que l’intention de ces promoteurs de l’Atomium fut bien de construire un symbole.

*

Tel qu’il est, l’Atomium est aussi le reflet d’un goût de notre époque: il correspond à ces innombrables récits de Science-Fiction dont certains (rares) sont excellents.

L’immense objet qui domine le panorama du Heysel parle plus à notre imagination qu’à notre raison. Il fait désormais partie de notre imagerie moderne que Jules Verne a génialement prévue, que Grandeville avant lui, avait devinée de façon plus âpre, plus poétique aussi.

L’étude photographique ci-jointe montre les rapports entre certains enfle de vue de l’ «Objet» et des images extraites de « De la Terre à la Lune » de Jules Verne et d’ « Un Autre Monde » de Grandeville, une fantasmagorie satirique qui l’un de ces jours reviendra à l’actualité.

Le romantisme du xixe siècle contenait déjà ce fantastique qu’aujourd’hui nous confondons avec réalité scientifique. Quelle singulière association de mots que Science-Fiction!

Me promenant dans la construction, j’ai eu beaucoup plus l’impression d’un voyage, d’un songe qu’une visite au sein du mystère de l’énergie atomique. (Pour cela il faudra attendre l’ouverture de l’Exposition, quand dans l’une des boules on nous montrera des films et sans doute un véritable matériel scientifique.)

On peut se croire là en bateau ou en ballon. Le plus étonnant est encore l’audace des hommes qui achèvent le montage de cette merveilleuse jonglerie.

M.B.

Marcel BROODTHAERS, « Un autre monde », Le Patriote illustré, Bruxelles, n°10, 9 mars 1958.

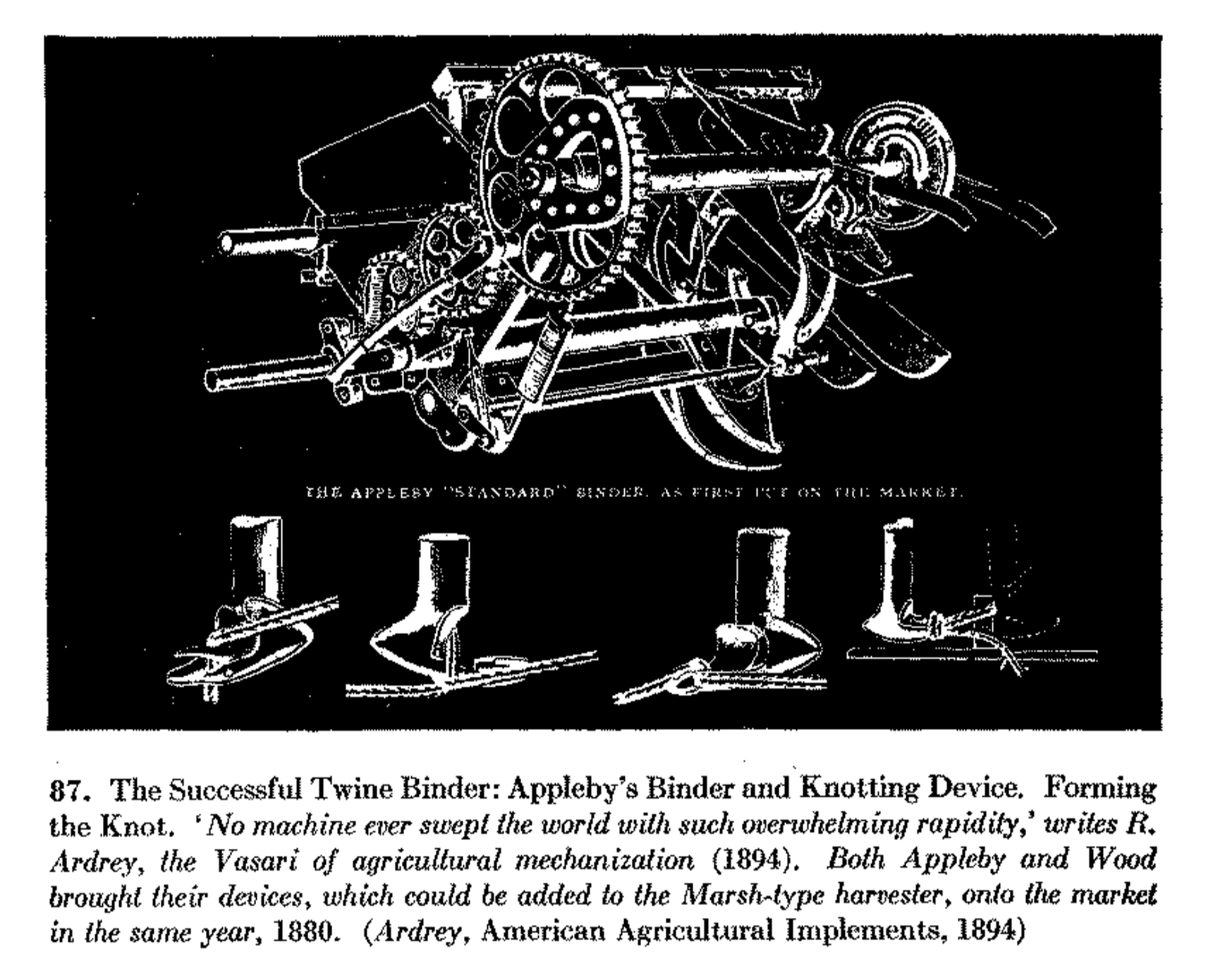

The automatic knotter. (around 1875): This machine, has more than any other, made it possible to increase production.

The automatic knotter. (around 1875): This machine, has more than any other, made it possible to increase production.

‘Balloonomania’ swept Britain in the last quarter of the 18th century, thanks largely to the exploits of the early aeronaut Vincenzo Lunardi. Following in the footsteps of the Montgolfier brothers in France, Lunardi arrived in London from Italy in the early 1780s determined to demonstrate the wonders of balloon-powered flight to the public. On the morning of 15 September 1784 nearly 200,000 people watched as Lunardi launched into the air in a hydrogen balloon, accompanied by his companions a dog, a cat and a pigeon, and drifted northwards for 24 miles before landing safely in Hertfordshire. For the next 50 years or so balloon flights across Britain became all the rage, drawing huge and expectant crowds whenever news of a launch was published, influencing science, literature and even fashions in the process. Pictured here is a public display of Lunardi’s balloon at the Pantheon in London, shortly after his maiden flight.

‘Balloonomania’ swept Britain in the last quarter of the 18th century, thanks largely to the exploits of the early aeronaut Vincenzo Lunardi. Following in the footsteps of the Montgolfier brothers in France, Lunardi arrived in London from Italy in the early 1780s determined to demonstrate the wonders of balloon-powered flight to the public. On the morning of 15 September 1784 nearly 200,000 people watched as Lunardi launched into the air in a hydrogen balloon, accompanied by his companions a dog, a cat and a pigeon, and drifted northwards for 24 miles before landing safely in Hertfordshire. For the next 50 years or so balloon flights across Britain became all the rage, drawing huge and expectant crowds whenever news of a launch was published, influencing science, literature and even fashions in the process. Pictured here is a public display of Lunardi’s balloon at the Pantheon in London, shortly after his maiden flight.

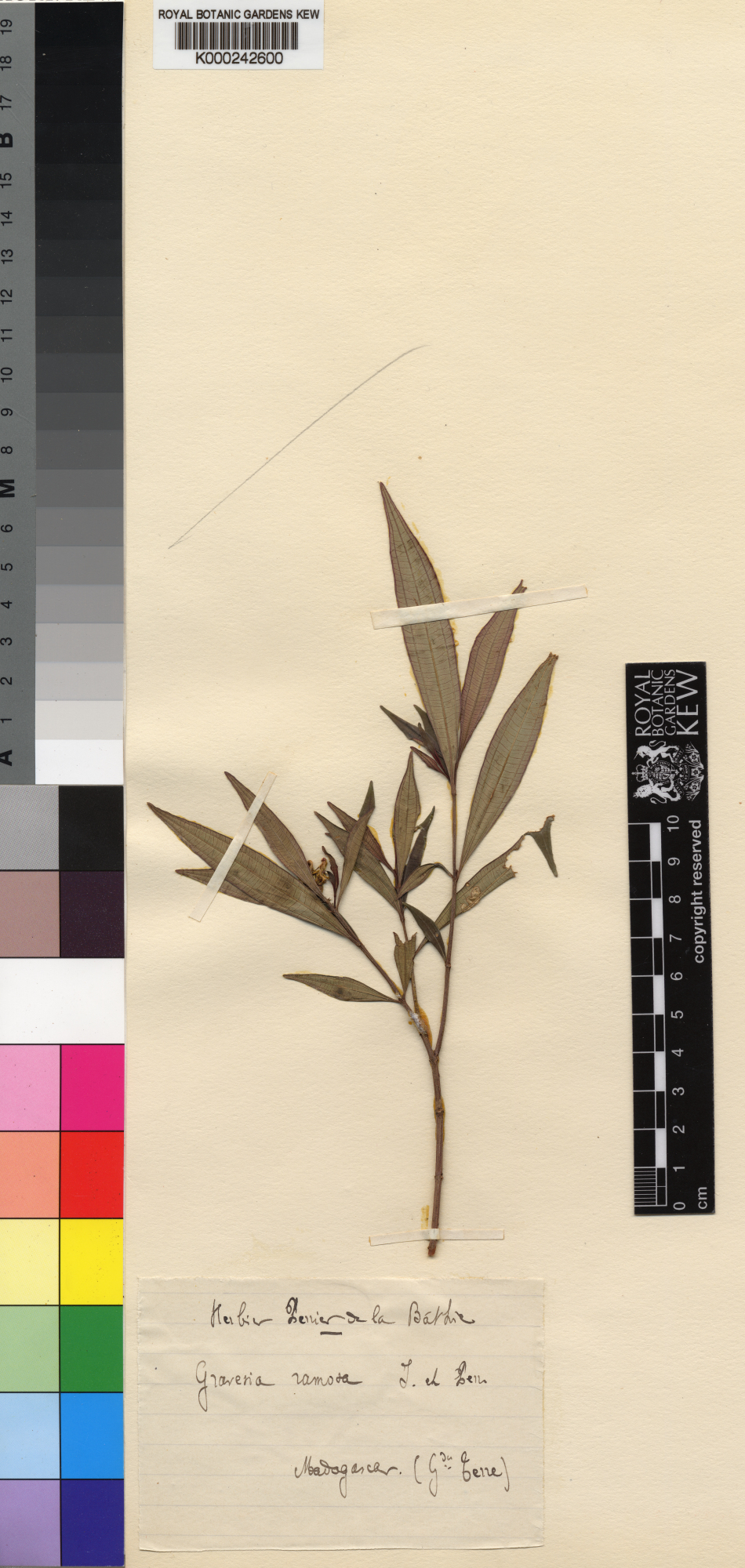

Identifiant: K/Herbarium/K000242600 http://specimens.kew.org/herbarium/K000242600 KXHERBARIUMXK000242600

Identifiant: K/Herbarium/K000242600 http://specimens.kew.org/herbarium/K000242600 KXHERBARIUMXK000242600