In 1944 Ken bought Eileen her first lightweight bicycle and, somewhat tentatively, they began riding with the Coventry Cycling Club. In that first season Eileen raced just once, in the club’s own ten mile time trial, turning up at the start without the regulation black jersey and shorts. A fellow club member lent her his black alpaca jacket and Eileen rode to victory, setting a new women’s club record.

In 1944 Ken bought Eileen her first lightweight bicycle and, somewhat tentatively, they began riding with the Coventry Cycling Club. In that first season Eileen raced just once, in the club’s own ten mile time trial, turning up at the start without the regulation black jersey and shorts. A fellow club member lent her his black alpaca jacket and Eileen rode to victory, setting a new women’s club record.

“I enjoyed racing,” she says now. “I loved the thrill of chasing. I just had to try hard and win. It was just in me to chase; I think you’re born with that.” In 1945, her first full season as an amateur, she won the national 25 mile time trial championship. The following year her son Clive was born but she was back training within seven weeks. As a racer, Eileen showed the same fearlessness that had seen her ride her aunt’s bicycle into the centre of Coventry as a seven-year-old. The saddle was far too high for her so she bobbed up and down on the pedals peering over the handlebars to see where she was going. She was spotted riding in between the tram tracks down Broadgate, the city’s main thoroughfare. When her parents found out they told her in no uncertain terms that this was an adventure not to be repeated.

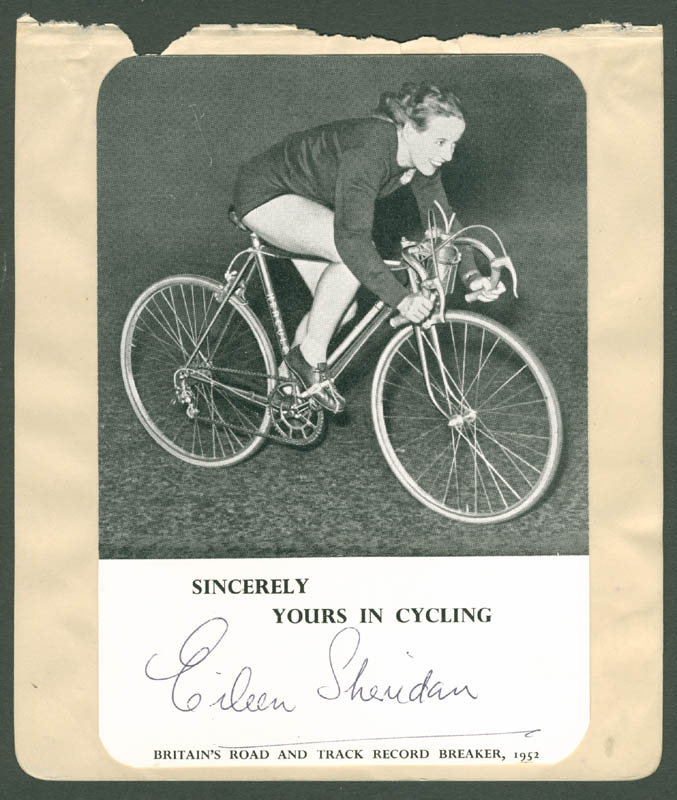

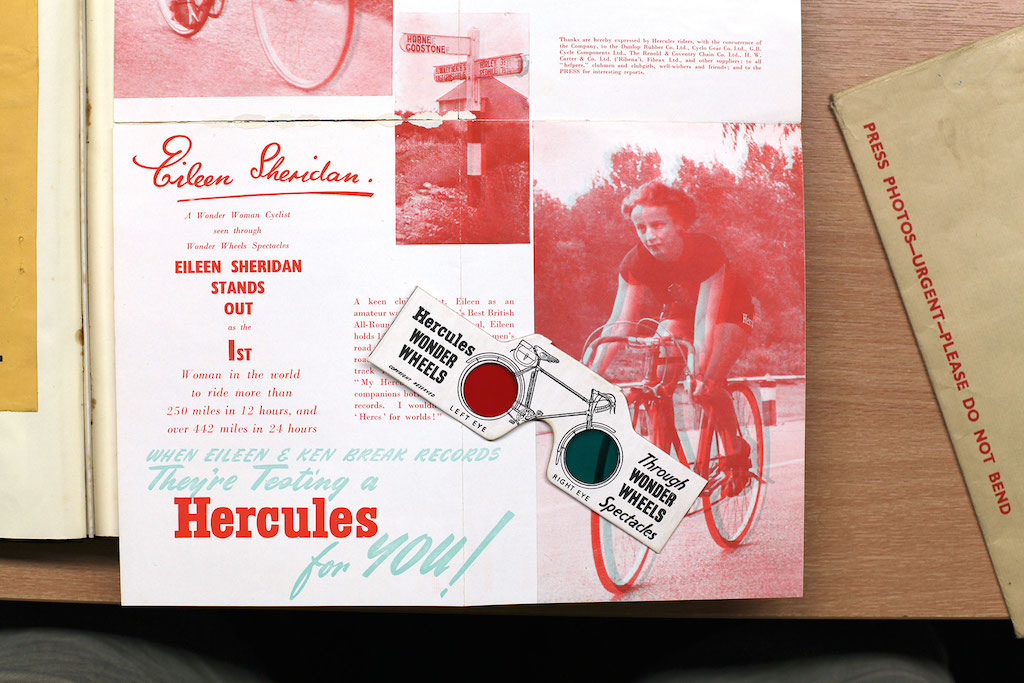

Newspapers dubbed her ‘The Mighty Atom’ and Sir Adolphe Abrahams, the founder of British sports medicine, wrote a feature in Cycling detailing her lung capacity, heart rate, musculature, psychological profile and other factors that combined to make “a human machine of the highest grade capable of superlative performance”.

Newspapers dubbed her ‘The Mighty Atom’ and Sir Adolphe Abrahams, the founder of British sports medicine, wrote a feature in Cycling detailing her lung capacity, heart rate, musculature, psychological profile and other factors that combined to make “a human machine of the highest grade capable of superlative performance”.  The advertisement is one of many now preserved with the rest of Eileen’s papers at the Coventry Transport Museum: carefully compiled scrapbooks filled with photographs, yellowing newspaper clippings and other ephemera. Besides the scrapbooks there is a box of trophies and medals and a pair of leather racing shoes, so tiny they look more like ballet shoes than anything made for cycling.

The advertisement is one of many now preserved with the rest of Eileen’s papers at the Coventry Transport Museum: carefully compiled scrapbooks filled with photographs, yellowing newspaper clippings and other ephemera. Besides the scrapbooks there is a box of trophies and medals and a pair of leather racing shoes, so tiny they look more like ballet shoes than anything made for cycling.

_______________

Entre perversion et moralisation :

Les discours médicaux au sujet de la pratique physique et sportive des femmes à l'aube du XXe siècle

Anaïs Bohuon

Des médecins affirment que le vélo et l’équitation peuvent détourner les jeunes filles d’éventuelles pratiques solitaires. « La femme qui recherche cette masturbation “bi-crurale” […], aurait bien évidemment bien d’autres moyens à sa disposition et nous croyons que l’exercice à bicyclette, bien loin d’entretenir ces manières vicieuses, les fera disparaître en améliorant l’état névropathique dont elles relèvent. On ne leur connaît pas de traitement plus efficace que l’exercice physique et la distraction » (Rocheblave, 1895 : 57). Les pratiques masturbatoires sont jugées pathologiques par ces médecins. Les pratiques physiques sont alors parfois envisagées comme des pratiques curatives, des pratiques qui vont permettre de contrôler, de guérir ce corps féminin si enclin à la pathologie.

Cependant, le discours assurant que la bicyclette et l’équitation peuvent sublimer les pratiques solitaires reste relativement rares. En effet, si les médecins citent le plus souvent la bicyclette comme un exercice physique pouvant générer des pratiques vicieuses, à l’inverse, ils y ont beaucoup moins recours lorsqu’ils évoquent la pratique physique comme pratique préventive à la masturbation. C’est alors la gymnastique, l’escrime et l’exercice physique qui sont présentés comme de possibles moyens d’empêcher la masturbation. La fatigue physique engendrée par ces activités diminue l’excitation nerveuse et détourne des pratiques solitaires. « Signalons, pour finir, une application des plus heureuses de la gymnastique. Contre les pollutions involontaires et l’onanisme, il n’est pas de plus sûr garant. De son côté, le docteur Mauriac range la gymnastique, l’escrime, un exercice quotidien allant jusqu’à une légère lassitude musculaire parmi les moyens préventifs les plus efficaces des pratiques solitaires » (Collineau, 1884 : 790-791).

Après avoir disculpé la machine en la rendant non responsable des pratiques vicieuses et accusé la cycliste, les médecins ont alors cherché par l’exercice musculaire « à faire baisser [la pulsion génésique] en intensité et à la faire dévier de sa trajectoire initiale pour l’investir dans un autre cycle de l’activité corporelle » (Dorlin et Chamayou, 2005 : 66). Si ces auteurs expliquent que l’exercice corporel est utilisé « pour éviter l’affaiblissement de l’organisme, il sert aussi directement, de façon positive, à viriliser le corps en le musclant » (ibid.), alors qu’en est-il pour les filles ?

Les hommes en effet ne se voient pas mis en garde de la même façon que les femmes. Les risques d’onanisme sont beaucoup moins évoqués et, lorsqu’ils le sont, ils posent moins de problèmes. Les médecins évoquent des répercussions du cyclisme assez différentes, les conséquences des trépidations étant au centre des questionnements : « celles-ci fatiguent-elles les muscles de l’érection ou, au contraire, en éveillent-elles les manifestations ? » (Baillette, 1986). L’enjeu ainsi n’est pas cette virilité du corps, mais simplement la procréation – faire « des mères ». Alors que ces corps féminins doivent être exercés pour mieux être gouvernés – les faire rentrer dans les normes corporelles féminines –, ils sont tout de même mis en danger par ces exercices physiques.

Ainsi, les médecins sont quelque peu pris au piège : ils se voient dans l’obligation de prescrire la pratique physique dans un souci de régénération de la « race ». Les femmes accèdent alors à la bicyclette, exercice qui est soupçonné d’engendrer des excitations génésiques. Même si dans les discours étudiés la question de l’orientation sexuelle ne semble pas remise en cause directement par la pratique physique, comment prescrire une activité masculine à des femmes sans qu’elles se virilisent ? Comment prescrire une activité associée, dans les représentations, à des comportements vicieux sans y tomber ? On trouve ainsi dans cette histoire médicale de la pratique physique féminine un schéma d’injonctions contradictoires – fais de la bicyclette pour être une bonne mère mais ne te masturbe pas, fais une activité physique (bastion masculin par excellence) mais ne te virilise pas… Les médecins ne peuvent pas tenter d’épuiser ces corps féminins pour les éloigner de ces pratiques de peur de viriliser ces corps et de les détourner de leur objectif primaire : l’enfantement.

Women Cycling Clubs

BY SHEILA HANLON

Many of the earliest ladies cycling clubs were formed as a reaction to gender inequality in clubs run by men, but they quickly took on a character of their own. Victorian ladies cycling clubs encouraged women to ride, allowed them to take full part in club life, expanded the geography of women’s cycling through group rides, and insulated women from the hostility they faced in public as lone riders. The all-female cycling clubs of the 1890s were more than mere leisure associations–they were a space where women worked collectively to protect their rights as cyclists and citizens.

Women’s cycling clubs were organised along similar lines to men’s cycling clubs. Most clubs were overseen by a council of officers including a president chosen for her social standing and dedication to cycling, a secretary or honorary secretary, a treasurer, and ride captains. Historian Patricia Vertinsky argues in her book The Eternally Wounded Woman that one of the LCA’s legacies was the fact that it “demonstrated that women were as good at working in associations as men.”

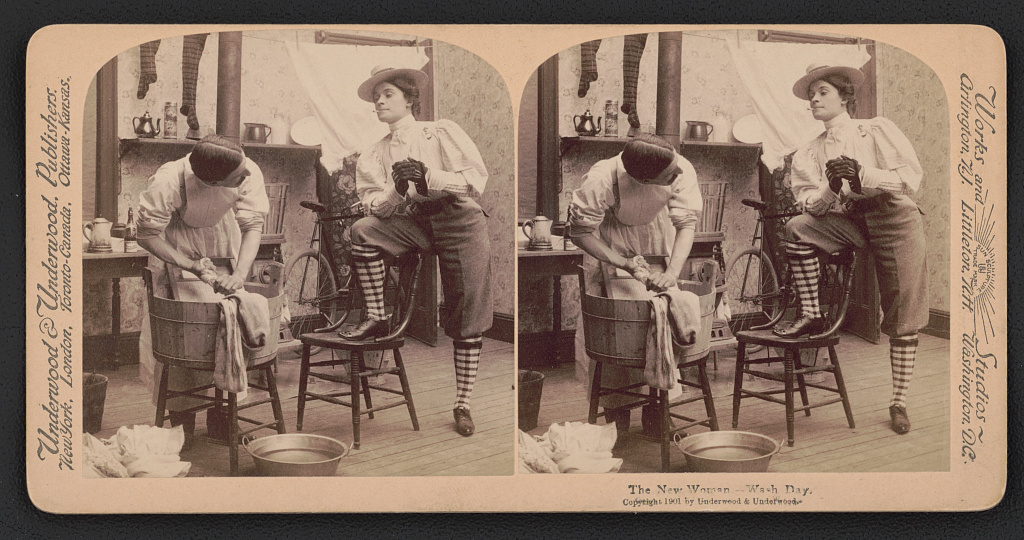

Title: The new woman--Wash day

Creator(s): Underwood & Underwood.,

Date Created/Published: New York ; London ; Toronto-Canada ; Ottawa-Kansas : Underwood & Underwood, Publishers, c1901.

Medium: 1 photograph : print on card mount ; mount 8.8 x 17.8 cm (stereograph format)

Summary: Stereograph showing a woman in knickers smoking cigarette and looking at man doing laundry.

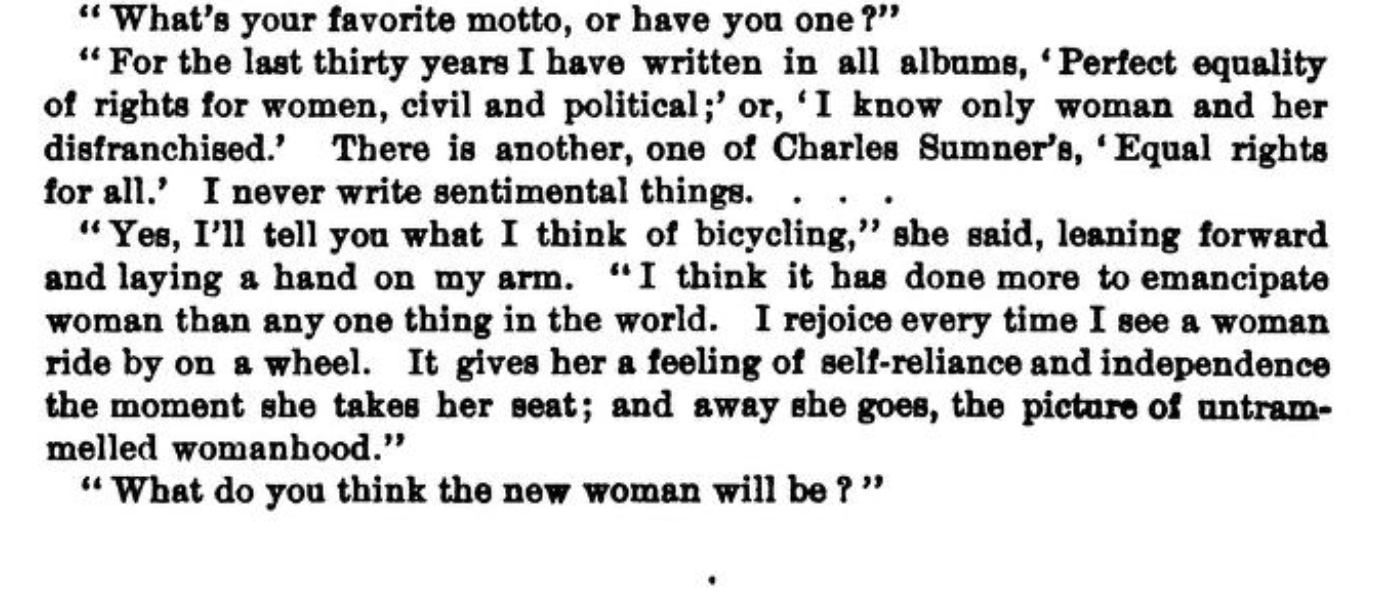

Leisure was central to ladies cycling clubs, but politics were never far behind. The political side of women’s cycling clubs began of course, with their endorsement of cycling for women which remained contentious in the 1890s. Rational dress was an unavoidable subject for women’s cycling associations, with clubs coming out both for and against it. In 1897, several clubs in favour of rational dress coordinated their efforts in a mass rational ride from London to Oxford for a meeting dubbed the “Congress of Rationals” by the press. About forty women and twenty men from The LCA, Ladies Rational Dress Cycling Club, Vegetarian Cycling Club, Ladies South West Bicycle Club, Yoroshi Wheel Club, and Western Rational Dress Cycling Club participated in the ride. The one rule of the event was that skirts would not be tolerated.

Leisure was central to ladies cycling clubs, but politics were never far behind. The political side of women’s cycling clubs began of course, with their endorsement of cycling for women which remained contentious in the 1890s. Rational dress was an unavoidable subject for women’s cycling associations, with clubs coming out both for and against it. In 1897, several clubs in favour of rational dress coordinated their efforts in a mass rational ride from London to Oxford for a meeting dubbed the “Congress of Rationals” by the press. About forty women and twenty men from The LCA, Ladies Rational Dress Cycling Club, Vegetarian Cycling Club, Ladies South West Bicycle Club, Yoroshi Wheel Club, and Western Rational Dress Cycling Club participated in the ride. The one rule of the event was that skirts would not be tolerated.

The political interests of women’s cycling clubs are apparent in the topics chosen for evening lectures and club newsletters. Dress reform, refugee rights, anti-vivisection, and of course suffrage were on the agenda. It was common for women’s cycling clubs to support causes through charitable drives, often for the benefit of needy members of their local community. The Clarion Cycling Club set the standard for charitable cycling drives with their well known Cinderella fetes, lantern rides, and parades in aid of poor children. The Clarion CC’s approach likely served as a model for women’s cycling clubs initiatives. The Leeds Ladies Cycling Club held a costume parade in aid of the New-Wortley Working People’s Hospital, while the Penzance Ladies’ Cycling Club focused fundraising efforts on soldiers’ widows and fatherless children.